DeLoggio Achievement Program

Selection of and Preparation for College and Professional Programs

The DeLoggio Philosophy of Education

The Decline of Excellence

Banning Genius

Of late, I have become obsessed with watching some great gymnasts and figure skaters of earlier years, and comparing them with more recent competitors. I find that as I study the mesmerizing moves of Olga Korbut or Kurt Thomas, the miraculous physicality they brought to their sport has never been equaled for one particular reason: their best moves have been banned from competition.

No one but Olga Korbut ever learned to have her balance go from her toes to the top of her head instead of stopping at her shoulders.

No one else had the strength of her back and shoulder muscles to use her head as a counterbalance, so that she could roll through a tumble in almost a complete circle. And when a few other young athletes broke their necks trying, Korbut's moves were banned from competition. Kurt Thomas's incredible precision of placement and total body control allowed him to do a half-dozen moves that his competitors couldn't match. The same was true of Robin Cousins' standing back flip while on figure skates. Too many people tried a move they were not ready for and wound up quadriplegic, and Cousins' moves were banned from competition.

The result, after two generations, has created a different kind of figure skater or gymnast. Rather than encouraging creativity, or spending the time to develop the peculiar sense of physical placement and development of certain sets of muscles to repeat the incredible, competition focused on limiting moves to the comfortably safe. Then, the athletes worked on building bigger muscles so that they can hold a safe handstand for a longer period of time, instead of developing a new art form. The strongest conformist gets the gold medal, and technical strength has been rated higher than artistry in the scoring.

The same thing is happening mentally, and we reward it and call it learning. No child left behind, read only these three books and memorize them, because that's what the state is going to test you on in May; learn to write the three paragraph essay; write shorter sentences so that you don't have to worry about misplaced modifiers or run-ons. Master mediocrity; creativity will reduce your score.

All of the planned learning that has overtaken first primary schools, then secondary schools, and now colleges – at least the public ones – is geared toward that "25/75" portion of the curve: work to eliminate the bottom, at the price of eliminating the top. And in the end you'll have a fine bell curve of the extent to which 10th-graders understood JD Salinger, and no idea at all of whether someone read May Sarton.

Celebrating Mediocrity

The post above is about banning genius – the exclusion from athletic competition and artistry of moves that were so brilliant that they were dangerous to less than superb practitioners of the art. Robin Cousins can do a standing back-flip on ice (and Surya Bonaly can do a back flip and land it on one foot!); other people can break their necks trying. So the move was banned from competition.

This post is about the opposite: taking people who really can achieve superior artistry and reducing them to a lower standard because lower equals more popular.

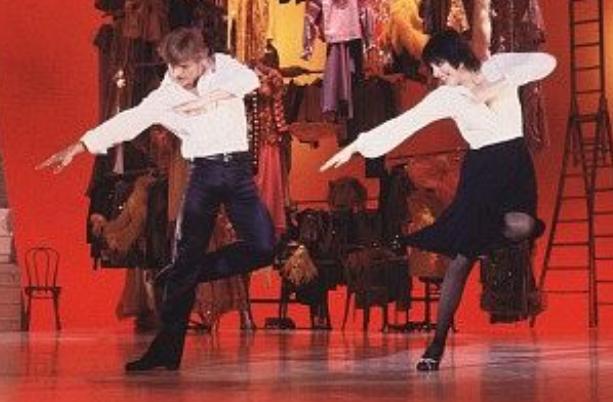

In this dance piece with Liza Minnelli and Mikael Baryshnikov, neither is using a quarter of their talent; but it's a "crowd-pleaser," reminding the audience of Hello Dolly, Cabaret, Sweet Charity, and a few other plays that I've never even heard of, even if the songs were memorable.

There was at least a decade on Broadway when Bob Fosse, Michael Bennett, and other top choreographers had died, and the London-based Andrew Lloyd Webber's musicals featured much more Greek chorus-style singing but very little dance, when the only thing playing on Broadway was revivals of “42nd St.“ and “Gypsy!” I saw them, but I can't think of a single story to pass on about them, and if you know me, that means they were pretty dull.

Choreography is returning to Broadway, in more avant-garde versions of Cabaret, and in the funky combinations of song and dance evidenced by"Movin' Out," "Rent," and "Hamilton." But the blockbuster shows have been Broadway reproductions of Walt Disney movies! And I wonder, as we see box office as a measure of quality, whether truly superior skill will ever win an award on "The X Factor."

What makes students successful?

The easiest way to become a successful student is to be genuinely interested in learning, and the easiest way to do that is to have parents who teach and encourage such activities. This can be accomplished by reading bedtime stories, by planting a seed and watching how a vegetable or flower can grow; it can be accomplished by taking apart broken toasters (or anything else that has mechanical parts instead of circuit boards) and seeing how machinery works.

|

|

Along with, or instead of, curiosity, there is the discipline of planned education. That means making the child do the homework, taking the time to sit with the child and make sure it's done correctly, helping the child participate in class projects, and doing it all with an attitude that tells the child this is cool and important, not a dreary chore that must be done because some stupid teacher said so.

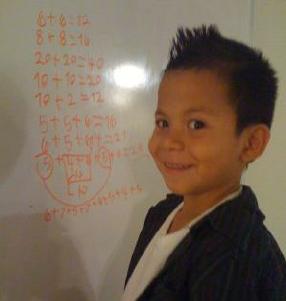

I think determination comes next: the willingness to complete a project even though you’re tired, or don't really want to go to the library one more time, or don't care whether "wether" is spelled correctly. That dreary adage, "anything worth doing is worth doing well," has to be taught. The concept that if you're thinking "good enough," you're almost certainly wrong, has to be explained repeatedly, starting at an age where a child can learn to do something again and try to do it better. In our family, that was at about age 5, and was equally true whether it was learning your letters and numbers, learning how to ride a bike, or coloring inside the lines.

As you get older, the concept of doing your best needs to be learned, especially the concept that "your best" will change over time, with practice, repetition, and conscious effort.

This piece took me about ten hours to carve.

If these basic rules of behavior, an ethics of learning if you will, are absorbed by the ages of 10 to 12, and if the child has really internalized them rather than just doing them because the parents forced them on the child, learning and being a success should have become a habit. And as we all know, habits are awfully hard to break.

Why Go to School?

A lot of people don’t know the many changes in the economy and how that affects the use of schools.

- In my mother’s era (1940s), the question was whether you could afford to graduate high school.

- In my generation (1960s), it was assumed you would graduate high school and go to work unless you were wealthy or an exceptional student. Wealthy people were expected to graduate college, and some would go for a graduate degree.

- In the 1970s, college got you a draft deferral, and the graduate degree was a life preserver.

- In my nieces’ generation (1980s), it was assumed you’d get at least a community college degree. The middle classes got a 4-year degree from a public school, and the wealthy went to a private school and headed for graduate school, especially the “professions” — medicine, law, business.

- By the mid-1990s, the booming middle class made the assumption of a four-year degree commonplace, but the emphasis on employment was bringing about the demise of the liberal arts colleges.

- The post-9/11 economic crisis made grad school a good shelter from unemployment; then, by the late 2000s, graduate school became “a waste,” as there were so few job openings.

- Since 2012, the economy has been improving, and the return to graduate and professional schools is evident, although children of immigrants and blue-collar workers are still keeping a close eye on the financial bottom line, and public schools and employment-track degrees (engineering, computer sciences, and the allied health professions) are preferred among the lower middle classes.

Education, its value to individuals and society, is ever-changing, and is a sign of social status as much as it is of intelligence and interest.

Young Man Reading by Candlelight” by Matthias Stom (fl. 1615–1649)

[Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

The DeLoggio Philosophy of Education

| Copyright | Take me to Home Page |