DeLoggio Achievement Program

Selection of and Preparation for College and Professional Programs

The DeLoggio Philosophy of Education

Curiosity Begins at Birth!

As I emphasize in my philosophy of education, learning can be thought of as memorization or as problem-solving; curiosity about how things work, what words mean, what something looks like, all tend to increase your likelihood of being prepared for an adult life, whether in school, in a job, or as the manager of a house and family. Children are born curious; learning is their basic defense mechanism against the dangers of the world. The more that children are encouraged to learn and explore, not by memorizing words and math problems on flashcards but by actually exploring the world around them, understanding the concepts behind the thing on the card, the more likely that child is to succeed in an American graduate or professional school, as well as at many jobs.

[Emily Blunt talks about the natural curiosity of her daughters.]

(There are a number of stories about job interviews at places like Microsoft in which the applicant walks into an office, and a problem is described, or a math problem is written on the board, and the applicant is encouraged to "think out loud" about the problem. The ones who have a positive and novel approach are most likely to be hired.)

|

|

Learning by exploring is something that children can begin at a very early age, if the parents encourage them to do so. Knowing that the baby will inevitably try the cereal bowl on as a hat, and that, messy as that may be, it is a positive step in the child's development, is the first step on the road to a superior education. (A good step in parental problem-solving is learning to give the child an empty bowl to play with for a while.)

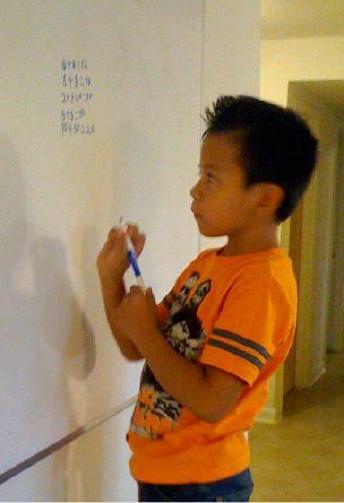

If a white board and colored markers make early learning more fun, Herman can have every color in the box! (He's standing on a step-stool to reach as much of the board as he can.) |

|

Origins of Phrases

One of my favorite "curious" games is the origin on phrases, and how the phrase changes as the reference dies. "In for a penny, in for a pound" made perfect sense in England, where everyone knew that a pound was a unit of money. Then Americans knew what a penny was but not a pound, and a pound turned into a euro, and the phrase became meaningless. Now you read things like, "In for a dime, in for a dollar."

I also like "give a damn," or "give a tinker's damn." A tinker was a tinsmith. A dam was a barrier or moat. The tinsmith would build a wall of dough to keep solder from running over. Once the solder was set, the dough was worthless. So "I don't give a dam" meant approximately the same as "I wouldn't give two cents for that."

Another favorite is a "baker's dozen," or thirteen. Bread was carefully price-controlled, and the typical sale was a dam a loaf or a penny a dozen. If the weight was short, the baker could be fined heavily, so he threw an extra roll into the bag to make sure he was covered.

I'm also a collector of misused idioms.

The phrase "Willy-Nilly" is often used to mean any which way, or chaotic. Instead, it means whether a person wants to or not. The original phrase, which I probably read in some book written in 1700, is "will he or nil he," "nil" being a variation of to choose not to do something.

Another one that surprosed me is "to the manner born." I thought the original phrase was "to the manor born," referring to the lord's house, or the upper-class element of society. Apparently, that's the basardization of the original phrase, a line in Shakespeare's "Hamlet" referring to habits.

What Makes You Curious?

My earliest memories of curiosity reach back to when I was about three years old, and they are all comical stories: the time Loretta put the bobby pin into the electric socket to find out what made the television work; the time Loretta filled the whole bowl with milk to try to figure out why the Cheerios were floating out onto the table; and the time Loretta spent a half hour asking Uncle Nicky about the lightbulb in the ceiling of his car.

|

|

Later curiosities destroyed my mother's music box, a clock, and a toaster. A half hour spent finding the switch that made the refrigerator lightbulb go on and off didn't kill anything, but I did get yelled at for letting all the food get warm.

But what my mother didn't do was discourage me from being curious. She learned to direct my curiosity towards things that were either indestructible or already broken. She taught me to read about things before I attacked them. She bought me those delightful wooden or ring-and-string puzzles. But she never, ever made the mistake of asking, "What difference does it make?"

The DeLoggio Philosophy of Education

| Copyright | Take me to Home Page |